As we have seen in Part I, ‘gyldig’ and ‘gældende’ are two central concepts of the theory of law and of legal norms that Ross tried to advance in ORR. Most of the translations of these concepts make the mistake of translating them both as ‘valid’ or ‘validity’, completely misrepresenting Ross’ argument and theory.

There is one exception though: the translation in Spanish made by Genaro Carrió in 1963.

Let us explore this here, and then look at the new English translation of 2019.

The Carrió translation – Spanish translation (1963)

The Argentinian translation of ORR into Spanish was different from the previous ones into English and Italian. Carrió was very careful when translating the text and, although he based his work on the English translation, he remained in constant contact with Ross to avoid mistakes.

Ross himself acknowledged this in a published article – that the 1958 translation problematic and that ‘gældende’ is translated as ‘vigente’ (an approximate translation into English would be ‘in force’) in the ‘63 translation of ORR.

Ross in Argentina and the beginnings of the Spanish translation

Carrió met Ross when the latter was delivering a series of lectures at the University of Buenos Aires (UBA), in Argentina. As mentioned in Part I, Ross went to Buenos Aires invited by Ambrosio Gioja, the chair of legal philosophy. Ross was impressed by how many people the Chair had (almost 100 in total), when he was almost alone in Copenhagen, and also by the quality of the discussion and knowledge of the young Argentinian legal philosophers.

One of the topics of discussion was the whole ‘gældende’ business. It was arranged for Ross to publish an article in the Revista Jurídica de Buenos Aires trying to, among several other things, put matters straight regarding the English 1958 translation (you may access a scanned version of the journal here). At this point, he started a series of communications with Carrió regarding a possible translation of ORR into Spanish, and how to properly deal with the ‘gældende’ problem. That translation was published in 1963; there, the problem is dealt with properly, in direct and constant consultation with the author.

The separate choices for ‘gyldig’ and ‘gældende’

‘Gældende’ for Ross is ‘in force’ – but not in a purely sociological sense, which can be confused with the law that is actually applied (which in turn can overlap with some meanings of ‘gyldig’). It is ‘in force’ in the sense of recognition of the legal norms that are used as justifications for legal decisions. Carrió takes great care with these notions and keeps both ‘gyldig’ and ‘gældende’ clearly apart both in meaning and in the Spanish terms used to express those meanings.

When Ross first presents this idea in ORR, he uses the example of the rules of chess. In the case of chess, the rules that are in force (‘gældende’) are those rules that are recognised by chess players who are truly committed to the practice of chess as justifications of the moves that one makes in the game. One must have a kind of mental predisposition towards the game in order to be a chess player. This, for Ross, is something like an internal point of view – but without rejecting the psychological aspects of such a point of view, as for example H.L.A. Hart does.

In the case of law, for Ross, this internal point of view is that of legal science. It recognises that certain rules of the legal system are in force – the law-in-action – because said legal norms are used by judges as justifications for their decisions. Those legal norms are in force because of how judges use them – not because of the recognition of legal science, mind you. Legal science merely records a fact: that a set of legal norms are actually in force.

In conclusion, this technical notion of ‘gældende’ is very different from the mere colloquial use of the colloquial use of ‘validity’.

The consequences of the choices for ‘gyldig’ and ‘gældende’

In addition, this shows how wrong choices in translation can truly ruin the content of the message.

The English edition of 1958 and its choice of translating both terms without qualification as ‘valid’ led to a scathing review by Hart, not only of ORR but of Ross’ entire theoretical project, as the translation conflated formal legal validity with the phenomenon of law in force that Ross was trying to describe.

There is only one way to put it: the English edition of 1958 is, on the whole, inadequate. It destroyed Ross’ work for the English-speaking world.

The second English translation (2019) and the persistence of the ‘gældende’ affair

Another English edition of ORR was needed, and this one appeared in 2019, translated by Uta Bindreiter and edited by Jakob v.H. Holtermann.

However, this 2019 translation has problems (again!) with the notions of ‘gyldig’ and ‘gældende’.

‘Gyldig’ and ‘gældende’: finally separated…

As can be seen by perusing the English 2019 translation, the term ‘gældende’ is translated as ‘scientifically valid law’. In many cases, it appears as ‘scientifically valid (x) law’, where ‘x’ is the place where the law has this “scientific validity”. For instance, “Scientifically Valid (Danish) Law”.

The editor states that this approach was chosen because it avoids confusing Ross’ theory with crude empiricism. In his words:

The problem with using law in force or existing or efficacious law is that these alternatives invite too crude or rigidly empiristic a reading of Ross’s realism. As explained in the introduction, one attraction of Ross’s theory is precisely that he manages to devise a consistent programme for an empiristic legal theory without succumbing to simplistic reductionism, and, in particular, without ignoring what Hart has called the internal aspect of law. Even if judicial behaviour is indeed a central element of Ross’s scientific concept of valid law, he demonstratively does not commit the empiristic fallacy of directly reducing law to such behaviour. On the contrary, Ross is keenly aware that law is a normative phenomenon and that any workable scientific concept of validity, even one based on an explication, must reflect that fact. By choosing, as a translation of gældende ret, words like law in force, or existing or efficacious law, which point only to outwardly observable facts, and which unlike gældende do not have the same root as the ordinary word for valid (gyldig), it would be easier to overlook this important element of moderation and sensitivity toward the normative in Ross’s theory.

… but not how it should be!

In my opinion, this does not hold up for several reasons.

The impossibility of such confusion

First, as we have seen before, Ross defines the term ‘gældende’ in a stipulative or explanatory manner in order to avoid the confusion mentioned by the editor.

No ‘validity’ (even scientific one) for ‘gaeldende’

Second, ‘validity’ is not an appropriate term to fix to ‘gaeldende’. This is because Ross, here, is not referring to the several meanings of ‘validity’ but to the fact that legal science records that the judges of legal system x use legal norm y to justify legal decision z. That is not any kind of ‘validity’ used in legal science, either ‘scientific’ or not. Therefore, a person who has an adequate use of legal language should not fall into the confusion mentioned by the editor. Using ‘validity’ for both ‘gyldig’ and ‘gældende’ does not consider some subtleties of legal language that are better kept apart.

For instance, a legal norm may be in force in legal system x (‘gældende’) without belonging formally to legal system x (‘gyldig’) because it has been repealed, for example, but still regulates past events that judges have to decide upon. Or a legal rule may be valid law in legal system x (‘gyldig’) but without being used by judges of said legal system to justify any decision in any case in said legal system (‘gældende’) because it regulates an exceptional and unlikely situation, such as Alchourrón and Bulygin’s example of taxes on large fortunes in extremely poor countries, which the judges of said system will probably never would have the chance to pass sentence on. Calling both this ‘gyldig’ and ‘gældende’ situations “valid” blurs the distinction that Ross as trying to make, making the same mistake as the translation of 1958.

It is neither beautiful nor ordinarily accurate

Thirdly, as a translation, it is horribly unattractive. But, more importantly, it seems to go against of the common meaning of the term ‘gældende’ in Danish.

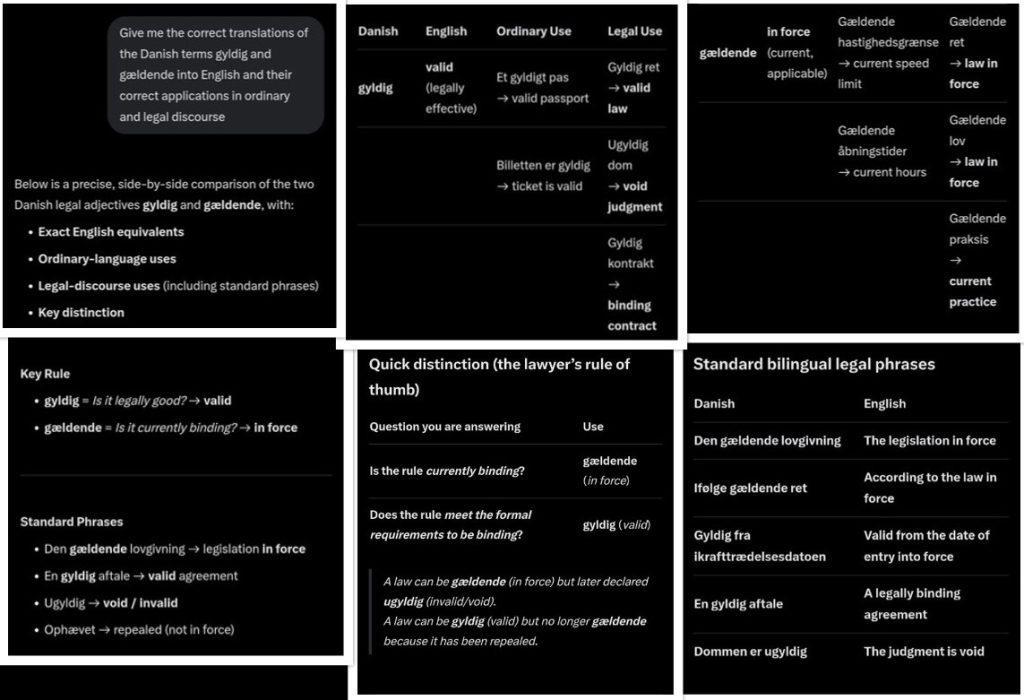

In regard to the latter, if we ask a language model about this (for instance, Grok and ChatGPT), this is what it has to “say”:

(these images correspond to an inquiry made to Grok, and its reply, on 04-11-2025)

The translation of ‘gældende’ as either ‘valid’ or ‘scientifically valid (x) law’ is contrarian to common and legal uses of the term. But, as we have seen, Ross defined ‘gældende’ in a stipulative manner, although close to legal usage. Does ‘scientifically valid (x) law’ runs against what he was trying to say?

We need to remember, for Ross, ‘gældende’ is the set of legal rules of legal system x recognised as being in force in legal system x by the legal science of x because the judges of x use those legal rules as justifications for their decisions.

The ‘validity’ – whatever that could mean here – does not come about because of a ‘scientific’ endeavour.

It comes about because the judges use said norms as a justification for a decision (or a set of decisions). Legal scientists merely record that fact. So, in a way, ‘scientifically valid’ is not wholly appropriate because i) we are not talking of validity here; ii) legal science does not cause that ‘validity’, it merely records it.

It goes against the choice of the author himself

Finally (there are more reasons, but it is better to stop here), Ross himself chose ‘in force’ as the translation of ‘gældende’.

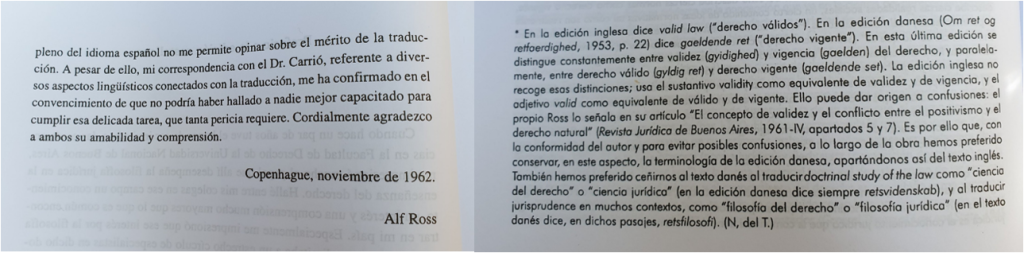

In 1961, he opted for ‘vigente’ and ‘efectivo’ when Carrió translated his essay ‘Validity and the Conflict between Legal Positivism and Natural Law’; and then, after consulting extensively with Carrió, he finally decided on ‘derecho vigente’ (‘law in force’):

This fact seems to be completely ignored in the explanatory note of the English 2019 translation (2019: li-lv). The essay that Ross published in 1961, in which he addresses this problem of the English 1958 translation, is not cited there. This seems quite inexplicable to me.

On the other hand, this essay is indeed mentioned in the editorial introduction. The question then is: why not use the term that Ross himself chose at the time? Is the chosen neologism not cumbersome enough? If it is for the reasons mentioned, I insist, they do not hold water.

The fact that Carrió’s translation of ORR is not mentioned at all in the introduction or in the explanatory note is something that is worth mentioning. In my opinion, the 1963 translation – which was also based in terminological choices Ross himself approved – could have helped a lot to translate this new English version in a more appropriate manner, being that it was the only one of several translations of ORR that was able to capture the intentions of Ross while developing his theory of legal norms.

A final remark

To conclude, I am not saying that the whole of the English 2019 translation itself is bad. Here, I am only saying that, for the reasons given, in my opinion the chosen translation of ‘gældende’ is unfortunate because is contrary to the way Ross himself chose to have the term translated in 1961; it is also contrary to his ideas on the matter; and it commits some of same mistakes as the English 1958 translation, such as attaching ‘validity’ (albeit here, with a qualification) to the notion of ‘gældende’.

SUGGESTED CITATION: Calzetta, Alejandro, “The ‘Gældende’ Affair – Part II”, FOLBlog, 2025/11/24,https://fol.ius.bg.ac.rs/2025/11/24/the-gaeldende-affair-part-ii/