We have already seen how logic has been applied in legal theory, in particular for the reconstruction of legal systems as deductive systems and the logical justification of legal decisions. Here, we will see in which sense the claim that judicial reasoning can be reconstructed as deductive has been criticised.

A criticism to the “legal syllogism” and some notes on defeasibility

Even accepting that the so-called ‘legal syllogism’ is a schematic reconstruction, a specific problem arises.

The logical implication “→” means that the antecedent is a sufficient condition for the consequent. This implies that given A → OB, whatever circumstance C is added to A, the conclusion OB still obtains: (A ∧ C → OB). This feature, known as strengthening (or reinforcement) of the antecedent, lies at the heart of what is referred to as the monotonicity of deductive reasoning.

Yet, in everyday reasoning – including legal reasoning – this property often seems counterintuitive. If someone commits homicide in self-defence, it seems inappropriate to conclude that the obligation to impose a sanction still follows. In other words: if certain circumstances are added, the conclusion may not follow or should not be applied. This general phenomenon is known as defeasibility.

From this perspective, the claim that judicial decisions can be reconstructed as a deductive reasoning has been criticised: that logical reconstruction would imply a kind of formalism because – as long as deductive consequences follow necessarily – the ‘legal syllogism’ would fail to allow for exceptions to legal norms or to give an account of the defeasible nature of legal reasoning.

Is this criticism sound?

This criticism steams from a sort of misunderstanding, and some clarifications are required.

First, it is important to distinguish between explicit and implicit exceptions.

Explicit exceptions

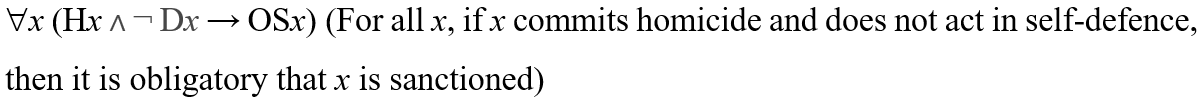

Returning to the self-defence example: in almost all actual legal systems, self-defence is explicitly recognised by a legal disposition as an exception to the general prohibition on homicide. The presence of such an explicit exception poses no challenge to the deductive reconstruction of judicial reasoning. It simply requires a reformulation of the norm in the first premise including the circumstance established as an exception in another disposition of the system. To do this, the antecedent of the first premise must be expanded adding as a negative condition the legal exception:

Under the reformulated norm, the conceptual content of the conditional is contracted (i.e. its scope is reduced).

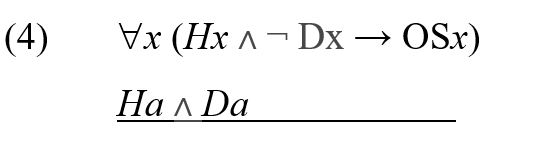

Suppose Mary killed someone in self-defence:

In (4) Modus Ponens is not applicable: note that there is no match between the antecedent of the reformulated norm and the second premise (“Dx” appears in the first premise with a negative sign, in contrast to “Da” in the second one), so conclusion OSa is not inferred. This methodology implies the revision of the antecedent, considering all the circumstances that the legal system explicitly provides as exceptions or defeaters.

Implicit exceptions

So far so good for explicit exceptions. Now, what about implicit exceptions? Should exceptional circumstances not explicitly stated or formulated within the legal system ever be considered as defeaters by interpreters?

Some “formalists” would answer that implicit exceptions are never admissible in law. However, if the answer is “sometimes” or “it depends” further questions arise: when, how, and on what grounds an implicit exception should be identified as such? Scholars who believe that legal reasoning is a branch of moral reasoning would suggest that underlying moral reasons may defeat a legal consequence. Legal positivists may accept that law includes implicit exceptions, but it remains controversial whether such exceptions should be (or could even possibly be) identified, enumerated or exhaustively listed in advance.

As you can see, defeasibility involves complex and controversial topics in legal philosophy. Logic cannot solve the dispute on the admissibility of implicit exceptions in law. What logic can do is help in dealing with exceptions in the reconstruction of legal reasoning once a defeater has been deemed admissible.

Defeasibility and legal principles

A final note on legal principles. Whether a legal principle can defeat a legal rule or not is a question that admits different answers depending on the assumed philosophical stances previously mentioned. When two principles come into conflict, balancing is the usual way to deal with it. However, from a logical perspective, balancing does not seem to be an appropriate way to justify judicial decisions, since it is an intellectual exercise aimed only at the specific case at hand. In this sense, it fails to provide a form of rational control over judicial decision-making.

Within a logical approach to law, conflicts between legal principles should instead be solved by establishing a conditional preference that applies to all individual cases in which the same circumstances are present. Only under this assumption would it be possible to talk about subsumption and so to justify the application of one principle over another as the legally right answer to a case.

To read more about this, check out this article: Scataglini, M. Gabriela, “Logic in Law: The Positivist School of Buenos Aires”. In: Sellers, M., Kirste, S. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6730-0_1109-1

SUGGESTED CITATION: Scataglini, M. Gabriela: “Does logic have any relation to law? (Part I)“, FOLBlog, 2025/7/29, https://fol.ius.bg.ac.rs/2025/07/16/does-logic-have-any-relation-to-law-part-ii/